Have a question not answered below? Get in touch.

1. Why isn't Circadin (prolonged-release melatonin) licensed for use in children whilst Slenyto (prolonged-release melatonin) is?

Your Subtitle Goes Here

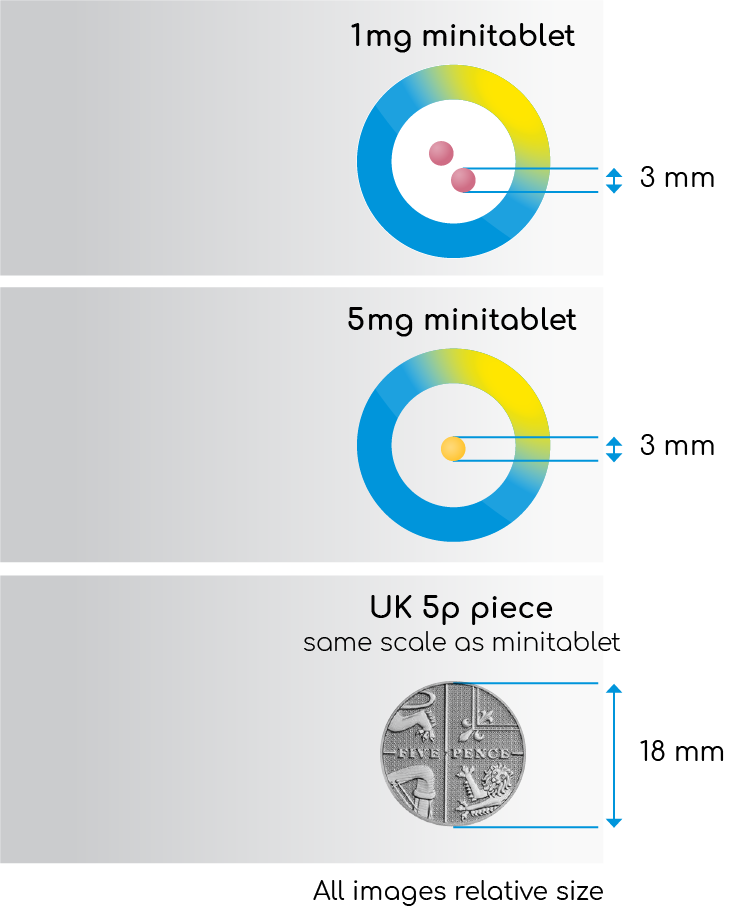

The size and shape of a tablet are fundamental to the ability of a child to swallow it. Therefore, the acceptability of the size and shape of tablets by the target age group(s) should be justified, and where relevant, supported by appropriate studies or clinical evidence. It should be noted that limited data are available in the literature regarding the influence of size, shape, and the number of tablets on acceptability in different paediatric age groups. For chronic diseases, the acceptability of tablets with a particular size and shape, in children, may be improved by adequate training. Tablet size and shape acceptability may also be improved by adequate instructions for co-administration with semi-solid food. Where tablets are not intended to be swallowed intact, e.g., dispersible, chewable, or effervescent tablets, considerations specific to tablet size and shape are of lesser importance. However, palatability issues may significantly affect the acceptability of these tablet types. Small tablets containing a fraction of the required dose may be considered as a measure to improve both the acceptability and/or dosing flexibility of tablets. Such small tablets are designed so that the dose for children in the different target age group(s) is achieved by the intake of one or several small tablets (concept sometimes referred to as “mini-tablets”). If a dose requires several tablets to be taken to achieve one dose, the acceptability of the required number of tablets should be discussed and justified for the relevant target age group(s). Apart from the tablet size and shape, the suitability of tablets in children should be further justified in relation to different health conditions or disease development profiles. Relevant warnings should be included in the SmPC and PIL where tablets must not be chewed but must be swallowed intact.1

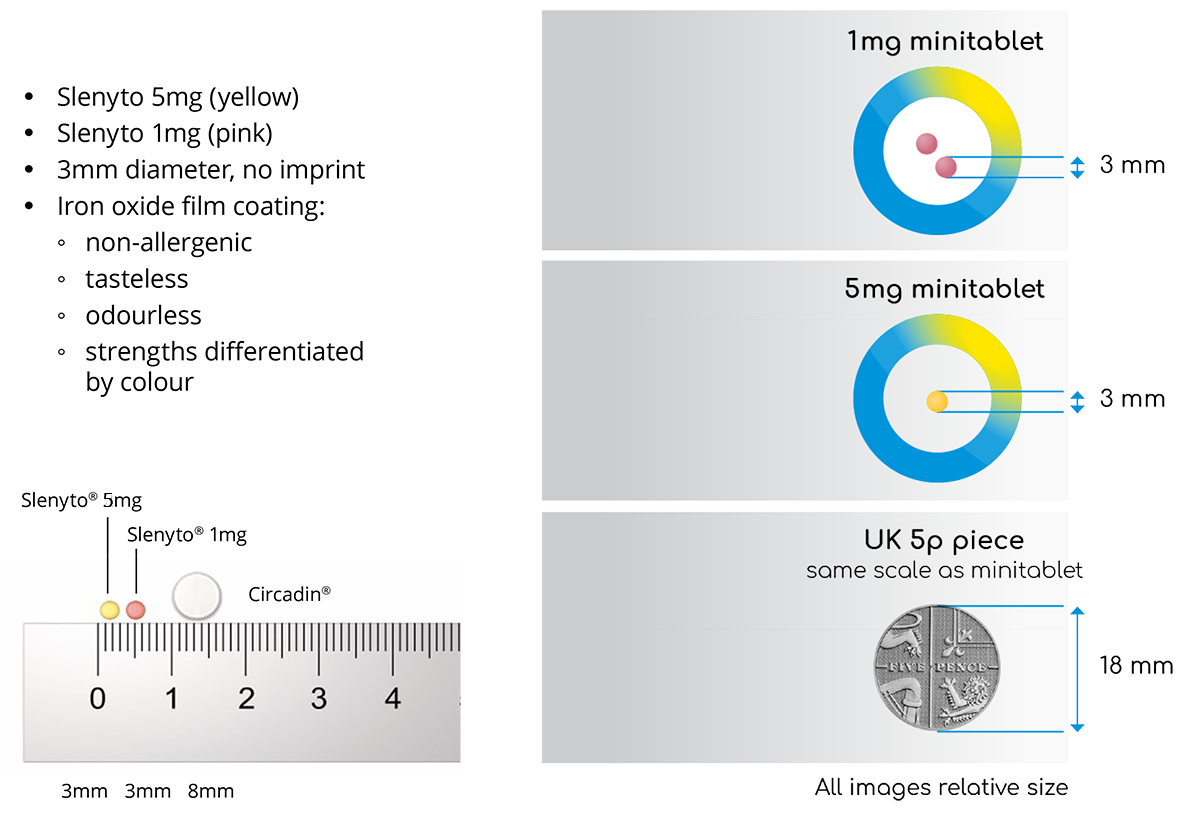

Circadin® (prolonged release melatonin 2mg) was developed to treat insomnia in patients aged 55 and older based on the well documented decline in an individual’s capacity to produce the endogenous hormone, melatonin, the decline in circadian clock output and the increase in complaints of poor sleep quality in older age.2 Circadin tablets are 8mm in diameter and cannot, therefore, be safely administered to young children. Until recently, however, there were no medications with regulatory approval for the treatment of chronic insomnia in children and adolescents and this was particularly problematic for children with ASD.3 Consequently, physicians often prescribe drugs off-label. For example, Circadin® is commonly used, albeit that to facilitate swallowing, the tablet is often sub-divided or crushed. In so doing, however, the intended release characteristics are destroyed, and the dose is effectively rendered immediate release and consequently less therapeutically effective.3

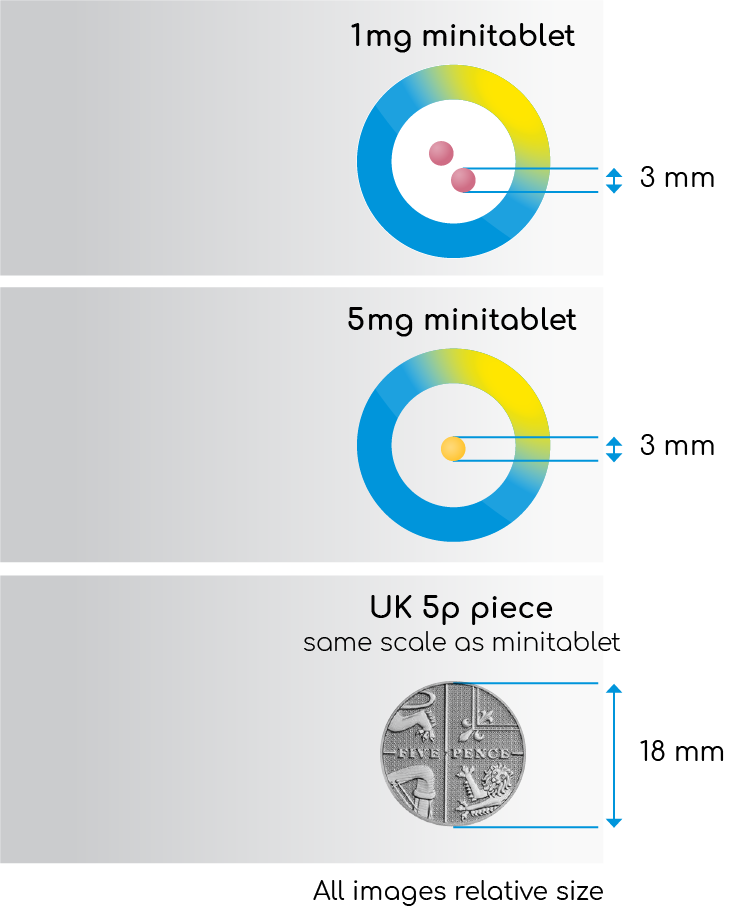

It is noteworthy that the licensing regulator, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), refused to consider an extension of the Circadin MA as they considered the formulation inappropriate for the intended population. The MA for Slenyto® is, therefore, a paediatric-use marketing authorisation (PUMA) which is a dedicated marketing authorisation covering the indication(s) and appropriate formulation(s) for medicines developed exclusively for use in the paediatric population. Unlike Circadin, Slenyto is formulated as an age (2-18) and disease-appropriate paediatric formulation of prolonged-release melatonin licensed for the treatment of insomnia in children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and or Smith-Magenis Syndrome (SMS).4 Children with ASD can present special challenges for drug administration and may present with unusual feeding difficulties, restrictive diets, dysphagia, and tactile sensitivities/defensiveness. Slenyto tablets are just 3mm in diameter and with an iron oxide film coating which is non-allergenic, tasteless, and odourless - see table 1. The Summary of Product Characteristics also provides further information on co-administration with foodstuffs to facilitate swallowing and improve compliance.4 The authors of the Slenyto registration seeking study noted that drug compliance was excellent.5

The availability of the 3mm Slenyto tablet (minitablet) allows for a dose (in the 2-10mg licensed range) with a maximum of two tablets. In contrast, the off-label use of Circadin to deliver a dose of 10mg, would require a dose of 5 x 2mg tablets each of 8mmm diameter with potential risks for safety, compliance, and the likelihood of need for manipulation of the dosage form.

Table 1. Slenyto Minitablet (All images relative size)

References

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-pharmaceutical-development-medicines-paediatric-use_en.pdf (Accessed November 2024)

- Wade, A.G. et al. 2007. ‘Efficacy of prolonged release melatonin in insomnia patients aged 55-80 years: quality of sleep and next-day alertness outcomes’, Current Medical Research and Opinion. 23(10), 2597-605.

- Chua, H.M. et al. 2016. ‘Dissolution of Intact, Divided and Crushed Circadin Tablets: Prolonged vs. Immediate Release of Melatonin', Pharmaceutics.8(1),2.

- Slenyto SmPC (Accessed November 2024)

- Gringras, P. et al. 2017. ‘Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder’, Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 56(11), 948-947.

2. Can a second dose of Slenyto be given if a child wakes during the night after giving an initial dose before bedtime?

Your Subtitle Goes Here

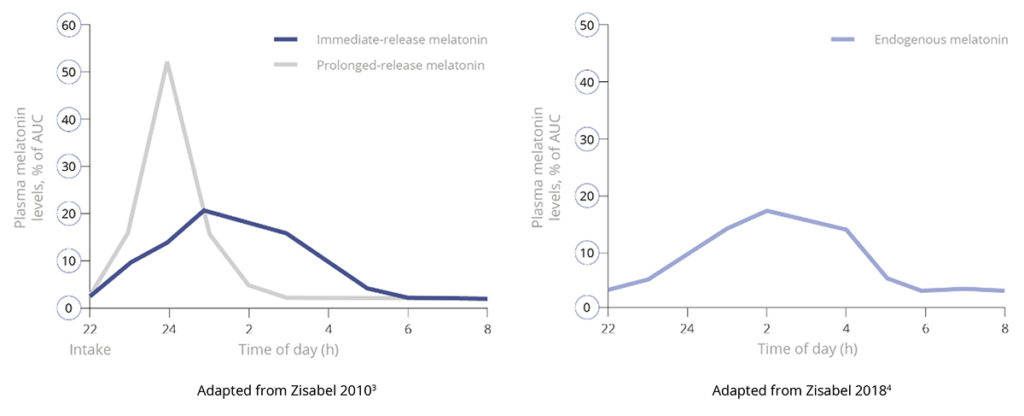

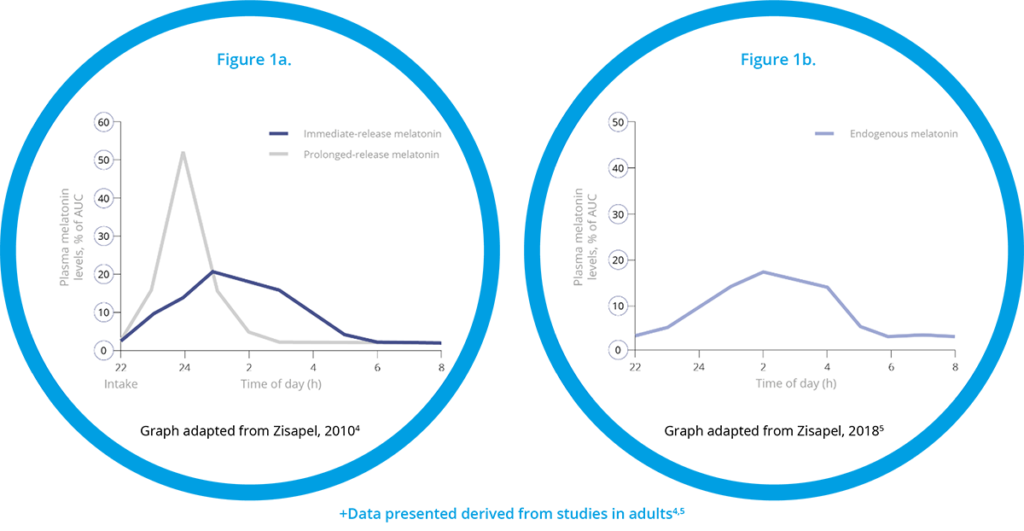

As a prolonged-release melatonin formulation, Slenyto is designed to mimic the endogenous profile by releasing melatonin throughout the night – see Figure 1. The clinical implications of the prolonged-release profile have been demonstrated in the registration seeking study which provided evidence of significant improvements, over baseline, in total sleep time, sleep initiation (latency) and maintenance, child behaviours (externalising), caregivers’ quality of life and resolution of their own sleep disturbance. Notably, improvements in total sleep time and sleep onset were not associated with earlier waking.2

Figure 1. Pharmacokinetic Profiles of Immediate, Prolonged-Release and Endogenous Melatonin*

|

|

| * Data presented derived from studies in adults. |

In summary, the prolonged-release design of Slenyto obviates the need for ‘in night’ dosing.

References

- Gringras, P. et al. 2012. ‘Melatonin for sleep problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: randomised double masked placebo controlled trial’, BMJ. 345.

- Gringras, P. et al. 2017. ‘Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder’, Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 28(10), 699-710.

- Zisapel, N. 2010. ‘Melatonin and Sleep’, The Open Neuroendocrinology Journal. 3, 85-95.

- Zisapel, N. 2018. ‘New perspectives on the role of melatonin in human sleep, circadian rhythms and their regulation’, British Journal of Pharmacology. 175(16), 3190-3199.

3. How can I measure sleep and define treatment goals in children with ASD and insomnia?

Your Subtitle Goes Here

There is little doubt that the investigation of sleep, or any other medical disorder, can be more challenging in this group of children, who may be disturbed by changes in the environment, or have sensory issues and poorly tolerate any monitoring.10 Sleep diaries are still the most commonly used subjective form of monitoring and, whether paper based or electronic (such as SNappD*), are easily completed and understood.10

A successful intervention needs to define realistic and agreed outcomes, in full partnership with the child’s carers and the child, where possible, that can be systematically monitored.5

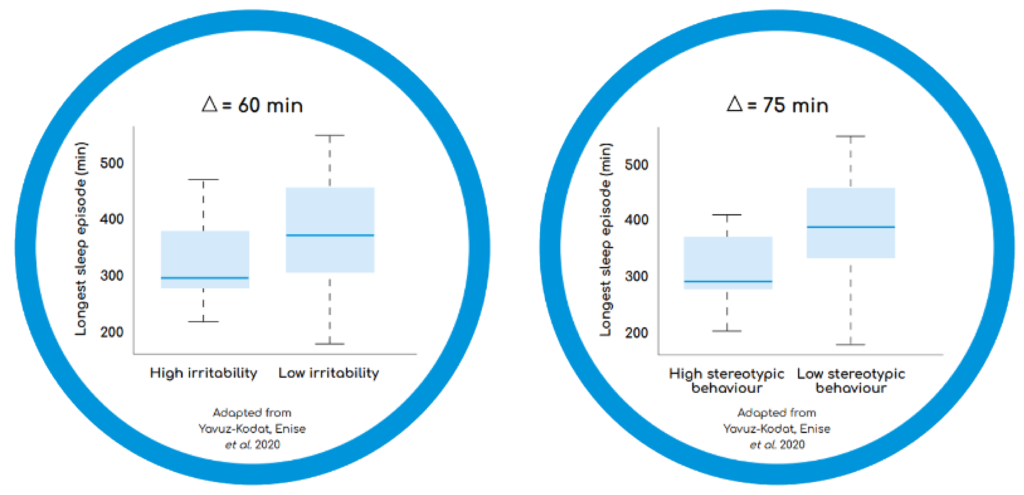

Sleep continuity (the longest continuous sleep episode: LSE) is an important sleep measure. Less than 6 hours of uninterrupted sleep has been associated with negative behavioural outcomes in children with ASD; children with high irritability and high stereotypic behaviours had shorter continuous sleep periods, compared to children with lower irritability, or less stereotypies (see Figure 1)9,10 LSE also correlates with changes in the child’s behaviours and parent’s quality of life.11

Figure 1. Longest Continuous Sleep Episode as a Function of Problem Behaviours in Children with ASD10

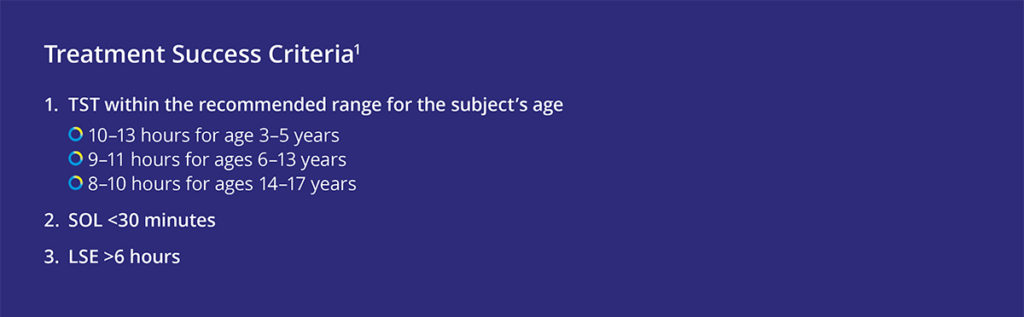

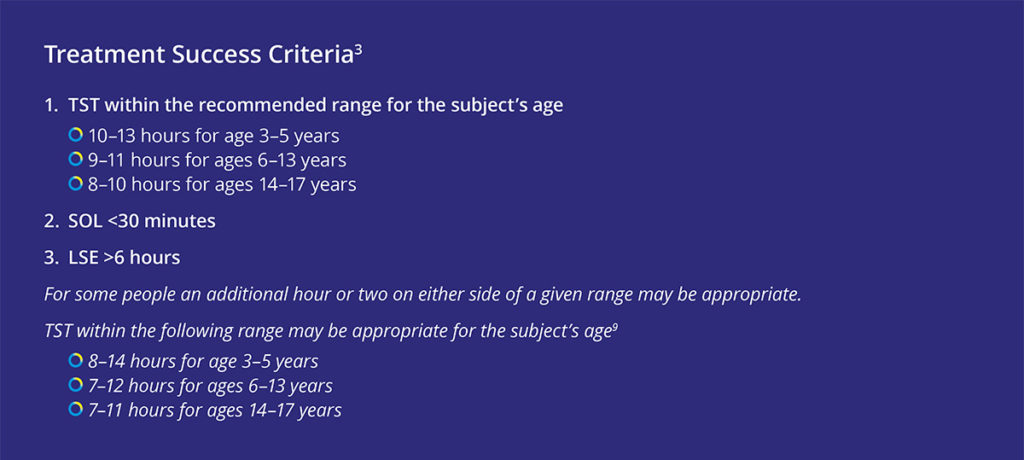

Another common measure is TST. Importantly, lower total sleep time is associated with poorer total and psychosocial paediatric quality of life in children with ASD.9 Whilst night awakenings are common in children with ASD, capturing them in a meaningful way is more difficult. There is a huge difference between 10 awakenings between 22:30 and 23:30 hours and 10 awakenings that occur every hour of the night. Thus, when evaluating the success of an intervention to treat insomnia in children with ASD consideration should be given to both improvement in total sleep time by age and the period of longest uninterrupted sleep - see table below12

In summary, failure to clearly agree defined treatment targets has not only impeded interpretation of much paediatric neurodisability research but can also hinder effective clinical management. The converse also applies.

*SNappD is a simple-to-use sleep and nap app that allows sleep statistics and the impact of poor sleep to be recorded. The app, which is based on a clinically validated questionnaire used by medical researchers and specialist sleep practitioners, can be downloaded from the iOS or GooglePlay app stores free of charge. Results from the app can be shared electronically with healthcare professionals to monitor progress. The Sleep Nap Diary app can be accessed via:

References

- Dahl, R. 2007. ‘Sleep and the Developing Brain’, Sleep. 30(9), 1213-19.

- Kotagal, S and Broomall, E. 2012. ‘Sleep in children with autism spectrum disorder’, Pediatric Neurology. 47, 242-251.

- Elrod, M and Hood, B. 2015. ‘Sleep Differences Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Typically Developing Peers: A Meta-analysis’, Journal of Developmental & Behavioural Pediatrics. 36(3), 166-77.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 2013. American Psychiatric Association

- McConachie, H. et al. 2018. ‘Enhancing the Validity of a Quality of Life Measure for Autistic People’, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 48(5), 1596-611.

- Bennett, A. et al. 2019. ‘Behavioural Concerns Associated with Sleep Disturbance Severity in Children with ASD’, INSAR. (Poster Presentation).

- Coury D.L, et al. 2019. ‘Association of Child and Adolescent Sleep Problems with Child and Parental Health’, INSAR. (Poster Presentation).

- Nguyen, A.K.D. et al. 2018. ‘Prospective Associations Between Infant Sleep at 12 Months and Autism Spectrum Disorder Screening Scores at 24 Months in a Community – Based Birth Cohort’, The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 79(1)

- Schroder, C.M. et al. 2021. ‘Padiatric prolonged-release melatonin for insomnia in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders’, Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy.

- Yavus-Kodat, E. et al. 2020. ‘Disturbances of Continuous Sleep and Circadian Rhythms Account for Behavioral Difficulties in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder‘, Journal of Clinical Medicine 9(6)

- Gringras, P. 2021. ‘Sleep in neurodevelopmental disorders’, European Sleep Research Society.

- National Sleep Foundation https://www.thensf.org/how-many-hours-of-sleep-do-you-really-need/ (Accessed November 2024)

4. What interventions are there for treatment of insomnia in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Your Subtitle Goes Here

Exogenous melatonin is most commonly used for sleep problems in ASD, related to the pathophysiology of insomnia in this population. In line with consensus recommendations that clinicians should offer pharmaceutical grade melatonin, if behavioural strategies have not been helpful, the development and regulatory approval of paediatric appropriate prolonged-release melatonin mini-tablets, Slenyto®, has been welcomed. For this indication, (insomnia treatment in paediatric ASD and/or Smith-Magenis Syndrome), Slenyto represents in-label use that provides the proof of quality, efficacy, dosing, and safety, including long-term efficacy, safety and acceptance needed for regulatory drug approval. The pharmacokinetic profile of Slenyto is of major importance for its ability to improve sleep onset, consolidation and duration in children and adolescents with ASD.1

Children with ASD can present special challenges for drug administration and may present with unusual feeding difficulties, restrictive diets, dysphagia, and tactile sensitivities/defensiveness. Slenyto is formulated as an age (2-18) and condition (ASD) -appropriate paediatric formulation; tablets are just 3mm in diameter and with an iron oxide film coating which is non-allergenic, tasteless, and odourless. The Summary of Product Characteristics also provides further information on co-administration with foodstuffs to facilitate swallowing and improve compliance.3 The authors of the Slenyto registration seeking study noted that drug compliance was excellent.4

The availability of the 3mm Slenyto tablet (minitablet) allows for a dose (in the 2-10mg licensed range) with a maximum of two tablets. In contrast, the off-label use of Circadin to deliver a dose of 10mg, would require a dose of 5 x 2mg tablets each of 8mm diameter with potential risks for safety, compliance, and the likelihood of need for manipulation of the dosage form.

Slenyto use is supported by 2-year clinical study data: its efficacy has been proven in both a 13-week randomised placebo-controlled study and a 91-week open-label trial. The trial demonstrated a clinically meaningful increase in total sleep time, reduction in sleep latency and an increase in the duration of uninterrupted sleep. By improving total sleep time and uninterrupted sleep, these outcomes underpinned improvements in day-to-day functioning and externalising behaviours positively impacting the wider family well-being and quality of life of patients’ caregivers/family members.4-7

The evidence-base for Slenyto and a guide for parents can be accessed via:

|

|

References

- Schroder, C.M. et al. 2021. ‘Pediatric prolonged-release melatonin for insomnia in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders’, Expect Opinion on Pharmacotherapy.

- Gringras, P. 2021. ‘Sleep in neurodevelopmental disorders’, European Sleep Research Society.

- Slenyto SmPC (accessed November 2024)

- Gringras, P. et al. 2017. ‘Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder’, Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 28(10), 699-710.

- Maras, A. et al. 2018. ‘Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder’, Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 28(10), 699-710.

- Malow, B.A. 2021. ‘Sleep, Growth, and Puberty After 2 Years of Prolonged-Release Melatonin in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder’, Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 60(2), 252-261.

- Schroder, C.M. et al. 2019. ‘Pediatric Prolonged-Released Melatonin for Sleep in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Impact on Child Behaviour and Caregiver’s Quality of Life’, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 49(8), 3218-30

5. How do I initiate treatment with Slenyto and optimise therapy?

Your Subtitle Goes Here

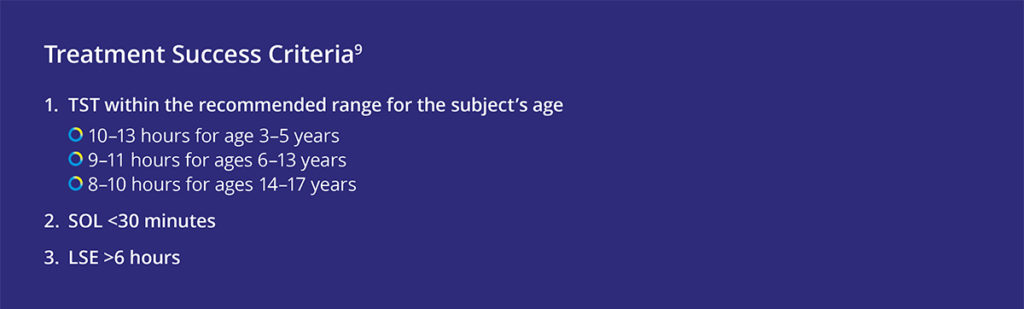

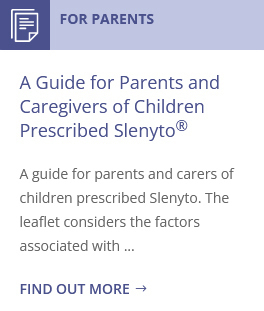

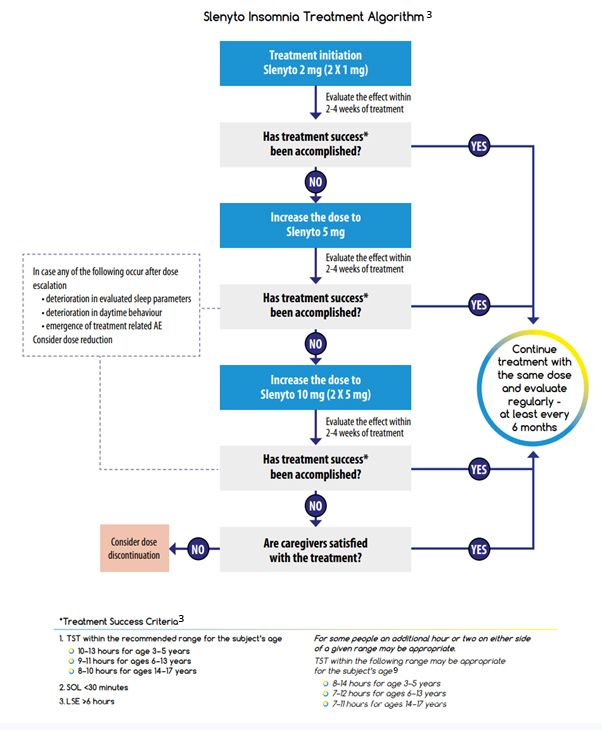

The recommended starting dose of Slenyto for children who fail sleep hygiene/behavioural intervention is 2 mg per day, with optional increase to 5 mg/day and then 10 mg/day. Dose adjustment is driven by the need to attain treatment success in one or more of the treatment success criteria (depending on the individual symptoms and severity).

It should be noted that the recommended age-dependent TST range can vary due to genetically driven factors. In addition, child behaviour, parent satisfaction with child’s sleep and safety should be considered in the decision to escalate or to continue the dose. If treatment success criteria are not achieved, despite a maximal dose of 10 mg, parental, or patient (if applicable), satisfaction should be considered before down-titration to a lower dose or stopping treatment.1, 2

For children using other medication to treat insomnia, e.g., antihistamines, alpha adrenergic agonists (clonidine), anti-psychotics etc., it is advised to taper them off before starting Slenyto. In case such medications are used for an indication other than sleep disturbance they can be maintained without major drug interaction problems. Immediate release melatonin may be stopped just prior to starting Slenyto.1

If treatment effects are reduced, daytime behaviour deteriorates or adverse events related to the drug (e.g., daytime somnolence) appear after dose escalation, the prescriber should first consider a down-titration to a lower dose before deciding on a complete discontinuation of treatment. Gradual loss of effect of melatonin after initial positive effect may occur in subjects with slow CYP1A2 metabolism, resulting in excessively high melatonin levels. In such cases, efficacy could be reinstated by tapering down the dose.1

The Slenyto Treatment Algorithm shown is also included in our Slenyto® Treatment Goals and Therapy Optimisation – A Guide for Healthcare Professionals

References

- Schroder, C.M. et al. 2021. ‘Pediatric prolonged-release melatonin for insomnia in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders’, Expect Opinion on Pharmacotherapy.

- Slenyto SmPC (Accessed November 2024)

- National Sleep Foundation (Accessed November 2024).

6. What are the advantages of using Slenyto versus liquid melatonin?

Your Subtitle Goes Here

Safety

Slenyto is an age (2-18 years) and condition-appropriate paediatric formulation of prolonged-release melatonin for the treatment of insomnia in children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder and/or Smith-Magenis Syndrome. The use of Slenyto in this population is supported by published evidence and approved in the licence particulars.1

An oral solution of immediate-release melatonin 1mg/mL is available.2 This product contains excipients (propylene glycol, sorbitol, and ethanol) which may be potentially problematic when used in children.13

Efficacy

All liquid melatonin preparations are immediate-release (IR) formulations with poor night-time cover resulting in poor sleep maintenance. Children treated with IR melatonin gain little additional sleep - they fall asleep earlier but wake earlier. Child behaviour and family functioning outcomes do not significantly improve.3

Slenyto, is paediatric formulation of prolonged-release melatonin designed to mimic endogenous melatonin production - see Figure 1.4,5

Figure 1 Pharmacokinetics of Immediate-Release versus Prolonged-Release Melatonin+

|

When used to treat insomnia in children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder and/or Smith-Magenis Syndrome for an initial period of 13 weeks children slept on average 57.5 minutes more per night and went to sleep on average 39.6 minutes earlier.6 After 52 weeks of continuous treatment, children slept on average 62.1 minutes longer (p = 0.007), went to sleep on average 49 minutes earlier (p<0.001) without earlier wakening.7

Besides shortening of SL, the observed increase in TST could be best explained by a greater improvement (increase) in the LSE compared to placebo. This is especially important for caregivers and families since a child who sleeps for 5 hours but wakes twice every hour is more disruptive to parents than a child who sleeps for 5 hours but wakes 10 times in the first hour. By the end of the 13-week double-blind period, the mean LSE increased on average by 77.9 minutes in the Slenyto treated group i.e., the LSE improved by over an hour.6

Importantly, and unlike IR melatonin, Slenyto did not result in earlier waking. In an earlier study of IR melatonin, a proportion of children fell asleep more quickly (i.e., SL was reduced) but also started to wake earlier (phase shifting).3 Slenyto improved both sleep initiation and sleep maintenance since it has been developed to mimic the endogenous profile and releases melatonin throughout the night - see Figure 1a and 1b

Slenyto 2 mg/5 mg treatment resulted in a significant improvement over placebo in the child’s externalising behaviours (hyperactivity/inattention and conduct scores) as assessed by the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)+ after 13 weeks of double-blind treatment (p=0.021).6 Using improvement (i.e. decrease) in externalising behaviours score by 1 unit or more as a criterion of clinical response, the percentage of responders after 13 weeks of double-blind treatment in the Slenyto group was 53.7% compared to 27.7% in the placebo-treated group (Odds ratio 3.0; p = 0.008), providing evidence for the clinical meaningfulness of the treatment effect. The 26% difference in percentage between the groups corresponds to an NNT of 3.8. For the total SDQ score after 13 weeks of double-blind treatment, there was a trend to benefit in favour of Slenyto (p=0.077).8 For social functioning (CGAS), the differences between Slenyto and placebo were small and not statistically significant.6

Figure 2. WHO-5 Caregiver’s Well-being and Quality of Life During the Double-Blind Period8

The treatment effects on sleep variables were associated with improved parents’ well-being. There was a significant improvement with Slenyto over placebo in Composite Sleep Disturbance Index (CSDI) -assessed parent satisfaction in child sleep pattern (p=0.005) and in caregivers’ well-being as assessed by the World Health Organisation scale (WHO-5) after 13 weeks of double-blind treatment

(p=0.01)1 - see Figure 2.

Adherence

Medication adherence refers to the person taking the prescribed medication, according to the prescribed dosage with the prescribed schedule for the prescribed treatment duration. A child’s refusal to take a medication, related to medication acceptability, is one of the most common reasons for non‐adherence in children.9

Medication palatability, defined as “the overall appreciation of an (often oral) medicinal product in relation to its smell, taste, aftertaste, and texture, is a main element of oral medication acceptability in children. Palatability of an oral medication is determined by the characteristics of both the active substance and the excipients.9 These factors are of particular importance in children with ASD since this population has documented tactile sensitivities, including issues with swallowing and excessive reactions to taste, smell, texture, or appearance of food.10,11

Melatonin 1mg/mL oral solution is a colourless to yellowish solution with a characteristic strawberry odour.2 The product also contains excipients (Propylene glycol, sorbitol, and ethanol) which may be potentially problematic when used in children.12

Slenyto is formulated to be both condition-(ASD) and age (2-18 years) appropriate and was developed to meet the needs of children with swallowing difficulties (young age) and/or sensitivities to touch, odour or taste (due to autistic core symptoms). Mini-tablets (1mg and 5mg) are odourless, flavourless, and just 3mm in diameter – easy to swallow, no need to crush1 - see Figure 3. The colouring agents used in the film coating are iron oxides and not generally considered to present a concern.

Figure 3. Slenyto (prolonged-release melatonin minitablets) 1mg and 5mg

|

"In contrast to the usual difficulties experienced by children with autism, compliance was excellent without the need to crush or dissolve."6 |

In contrast to the difficulties with conventional formulations experienced by children with autistism spectrum disorder, the authors of the Slenyto registration-seeking study reported excellent (almost 100%) compliance, without the need to crush, sub-divide or dissolve the mini-tablet (which would negate the prolonged-release properties).6

Succinctly, Slenyto offers the functional benefits of a liquid. in terms of ease of administration, whilst helping to avoid palatability issues, high levels of dosing errors and unacceptable excipients associated with some liquid formulations of melatonin.

Cost

Melatonin liquid 1mg/1ml is listed in the Drug Tariff (November 2022) at a cost of £157 /150ml.12

This has resulted in an increase spend on liquid melatonin from £4m in 2019 to approximately £18.2m per annum, to date.10

Melatonin liquid 1mg/1ml is 52% more expensive than Slenyto (comparative cost £1.05 versus £0.69 (per mg).

The average daily dose after 1 year of treatment with Slenyto in patients who responded was 5.3mg. Response = overall improvement ≥1 hour in TST, SL or both over baseline, and did not require dose escalation.

NHS list prices for the tablets are provided below

| Product | NHS List Price | Pack Size |

| Slenyto 1mg | £41.20 | 60 tablets |

| Slenyto 5mg | £103.00 | 30 tablets |

References

- Slenyto SmPC (Accessed November 2024)

- Melatonin 1mg/mL oral solution SmPC (Accessed November 2024)

- Gringras, P. et al. 2012. ‘Melatonin for sleep problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: randomised double masked placebo controlled trial’, British Journal of Pharmacology. 345.

- Zisapel, N. 2010. ‘Melatonin and Sleep’, The Open Neuroendocrinology Journal. 3, 85-95.

- Zisapel, N. 2018. ‘New perspectives on the role of melatonin in human sleep, circadian rhythms and their regulation’, British Journal of Pharmacology. 175(16), 3190-3199.

- Gringras, P. et al. 2017. ‘Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder’, Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 28(10), 699-710.

- Maras, A. 2018. ‘Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Released Melatonin for Insomnia in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder’, Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 28(10), 699-710.

- Schroder, C.M. et al. 2019. ‘Pediatric Prolonged-Released Melatonin for Sleep in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Impact on Child Behaviour and Caregiver’s Quality of Life’, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 49(8), 3218-30

- Lajoinie, A. 2017. 'Assessing the effects of solid versus liquid dosage forms of oral medications on adherence and acceptability in children (protocol)', Cochrane Library Issue 9

- Gazeley, H. 2017. ‘Dysphagia for people with Autism and Learning Disabilities’, Options. Issue 11

- NICE CG128

- Drug Tariff https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/pharmacies-gp-practices-and-appliance-contractors/drug-tariff (Accessed November 2024)

- PrescQIPP 245, May 2020

7. How do I know if I am adequately treating my patients with Slenyto?

Your Subtitle Goes Here

Part of the challenge is that there are multiple potential goals of treatment and multiple stakeholders. The clinician has to decide whether to address the sleep onset, continuity, total sleep time (TST), or combinations of them all. However, the greatest impact of a sleep intervention might be on a child’s daytime mood and concentration. Is the clinician treating the child’s sleep issues, or the sleep-deprived parents, or the older sibling whose sleep and schoolwork are affected?2

Sleep continuity (LSE; the longest continuous sleep episode) is an important sleep measure. Less than 6 hours of uninterrupted sleep has been associated with negative behavioural outcomes in children with ASD; children with high irritability and high stereotypic behaviours had shorter continuous sleep periods, compared to children with lower irritability, or less stereotypies.3 LSE correlates with changes in the child’s behaviours and parent’s quality of life.2

The pharmacokinetic profile of Slenyto is of major importance for its ability to improve sleep onset, consolidation and duration in children and adolescents with ASD.3

Slenyto use is supported by 2-year data: its efficacy has been proven in both a 13-week randomised placebo-controlled study and a 91-week open-label trial. The trial demonstrated a clinically meaningful increase in total sleep time, reduction in sleep latency and an increase in the duration of uninterrupted sleep. By improving total sleep time and uninterrupted sleep, these outcomes underpinned improvements in day-to-day functioning, cognitive performance and externalising behaviours, positively impacting the wider family well-being and quality of life of patients’ caregivers/family members.4-7

The response to melatonin is seen rapidly (within 1 week) allowing fast evaluation of treatment success and dose optimisation. Because the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of Slenyto are not predicted by age, body weight or puberty, the preferred dosing strategy is a personalised titration to optimal dose.3

The recommended starting dose of Slenyto for children who fail sleep hygiene/ behavioural intervention is 2 mg per day, with optional increase to 5 mg/day and then 10 mg/day. Dose adjustment is driven by the need to attain treatment success in one or more of the treatment success criteria (depending on the individual symptoms and severity).

It should be noted that the recommended age-dependent TST range can vary due to genetically driven factors. In addition, child behaviour, parent satisfaction with child’s sleep and safety should be considered in the decision to escalate or to continue the dose. If treatment success criteria are not achieved, despite a maximal dose of 10 mg, parental, or patient (if applicable), satisfaction should be considered before down-titration to a lower dose or stopping treatment.3, 8

If treatment effects are reduced, daytime behaviour deteriorates or adverse events related to the drug (e.g., daytime somnolence) appear after dose escalation, the prescriber should first consider a down titration to a lower dose before deciding on a complete discontinuation of treatment. Gradual loss of effect of melatonin after initial positive effect may occur in subjects with slow CYP1A2 metabolism, resulting in excessively high melatonin levels. In such cases, efficacy could be reinstated by tapering down the dose.3

The Slenyto Treatment Algorithm shown is also included in our Slenyto® Treatment Goals and Therapy Optimisation – A Guide for Healthcare Professionals

References

- McConachie H, et al., Enhancing the Validity of a Quality-of-Life Measure for Autistic People. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2018;48(5):1596-611

- Gringras P. Paediatric Sleep Disorders. European Sleep Research Society. 2021

- Schroder M, et al., Paediatric Prolonged Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children and Adolescents with Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2021

- Gringras P, et al., Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017;56(11):948-57.

- Maras A, et al., Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2018;28(10 SRC - BaiduScholar):699-710

- Malow BA, et al., Sleep, Growth, and Puberty After 2 Years of Prolonged-Release Melatonin in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 Feb;60(2):252-261.e3

- Schroder CM, et al., Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Sleep in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Impact on Child Behavior and Caregiver’s Quality of Life. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2019;49(8):3218-30

- Slenyto SmPC (Accessed November 2024)

- National Sleep Foundation. (Accessed November 2024).

8. If the starting dose of Slenyto is 2mg why is there a 1mg tablet?

Your Subtitle Goes Here

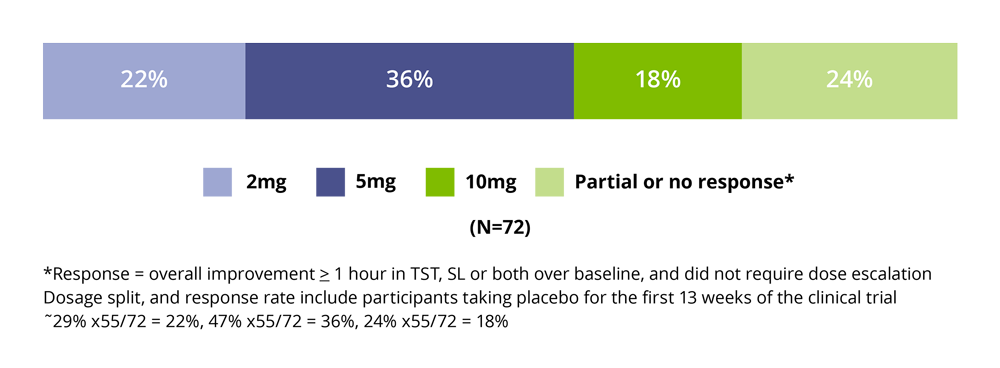

After 3 weeks of double-blind treatment, sleep variables were reassessed. If the patient did not improve from baseline by at least 1 hour, as measured by a shortening of sleep latency (SL) and/or increase in total sleep time (TST), the dose was escalated to 5 mg. Patients continued double blind on 2 or 5 mg of active or placebo for the remaining 10 weeks.1

A total of 95 participants who completed the 13-week double-blind phase entered the 39-week, open-label follow-up phase. Accordingly, patients who received 2mg placebo in the double-blind phase received 2mg Slenyto, and those who were escalated to 5mg placebo received 5mg active.2

After the first 13 weeks of follow-up sleep variables were assessed, and if the patient did not improve from baseline by at least 1 hour in sleep latency (SL) and/or total sleep time (TST) in the double-blind or follow-up phases, the dose was escalated from 2 to 5 mg/day and from 5 to 10 mg/day. An optional decrease in dose was also allowed at all times during the study, based on the evaluation of excessive drowsiness, behavioural changes, or ceasing to respond to study drug. Children then continued open label on 2, 5, or 10 mg for the remaining period, with efficacy assessment after 26 and 39 weeks of follow-up.2

After 52 weeks of continuous treatment 76% of patients achieved a clinically meaningful response (i.e., overall improvement ≥1 hour in TST, SL or both over baseline). Of the 55 responders, 22% (16 patients) used 2mg/day, 36% (26 patients) used 5mg and 18% (13 patients) used 10mg~. Seventeen subjects (24%) had partial, or no measurable, response compared with baseline even at the highest (10mg) dose. The average daily dose after 1 year of treatment in patients who satisfied this criterion was 5.3mg.2

Figure 1. Clinically Meaningful Response to Slenyto by Dose After 52 week 2

Figure 2. Slenyto (prolonged-release melatonin minitablets) 1mg and 5mg

|

"In contrast to the usual difficulties experienced by children with autism, compliance was excellent without the need to crush or dissolve."1 |

References

- Gringras, P. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(11):948-957

- Maras A, et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Jnl Child and Adolesc Psychpharmacol. 2018; doi 10.1089:1-12