In July 2018, Slenyto paediatric-appropriate prolonged-release melatonin tablets were granted a Paediatric Use Marketing Authorisation (PUMA).

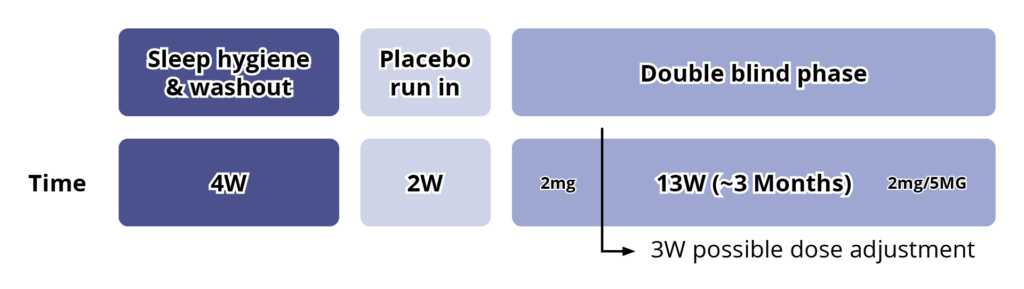

In the double-blind period, 125 children (2–17.5 years; 96.8% ASD, 3.2% SMS) with insomnia and without a documented history of sleep behavioural intervention at screening, underwent 4 weeks of advice booklet–assisted, basic, parent-led sleep behavioural intervention based on a previously studied and standardised sleep behaviour treatment. This period ensured that children whose sleep disorder was amenable to non-pharmacological management were not randomised, and also served as wash-out from any hypnotics.6

Eligible children entered a 2-week, single-blind, placebo run-in period after which, if they still had impaired sleep (defined as ≤6 hours of continuous sleep and/or ≥0.5-hour sleep latency (SL), from lights-off in 3 of 5 nights in the last 2 weeks, based on a parent-reported Sleep and Nap Diary (SND)), they were randomised (1:1), to receive active or placebo for the 13-week double-blind treatment period.6

The starting dose of active (or placebo) was 2 mg once daily, 30-60 minutes before habitual bedtime and with or after food. After 3 weeks of double-blind treatment, sleep variables were reassessed. If the patient did not improve from baseline by at least 1 hour, as measured by a shortening of SL and/or increase in total sleep time (TST), the dose was escalated to 5 mg. Patients continued double blind on 2 or 5 mg of active or placebo for the remaining 10 weeks, with an efficacy assessment by the end of the 13-week double-blind treatment period.6

See Figure 3.

Figure 3: Study Design6

The primary efficacy outcome in the 13-week study was the change from baseline in mean TST and a secondary outcome was change from baseline in mean SL.6

Other secondary sleep variables were:

- The change from baseline in duration of wake after sleep onset

- Number of awakenings, and longest (uninterrupted) sleep episode (LSE)

- Change from baseline in Composite Sleep Disturbance Index (CSDI) score and subscores

- Number of dropouts during the 13-week double-blind treatment period

The CSDI is a validated tool scoring the frequency and duration of sleep problems reported by parents. Safety was monitored throughout the study using standard clinical trial methods and definitions and standard age-appropriate methods were used to assess the child development and health status.6

After 13 weeks of treatment with Slenyto, children slept on average 57.5 minutes more per night and went to sleep on average 39.6 minutes earlier.6

Using the definition of clinical response as an increase in TST of ≥45 mins and/or reduction in SL by ≥15 mins versus baseline, 68.9% of participants responded to Slenyto by 13 weeks (versus 39.3% with placebo; p=0.001) corresponding to a number needed to treat (NNT) of 3.38. Thus 2 out of 3 children with ASD are expected to have a clinically meaningful response to a 2/5 mg dose.6

Whilst the number of participants with an SMS diagnosis were too small to extrapolate the benefits to the population as a whole, these findings do demonstrate improvements in externalising behaviours which might be particularly beneficial in SMS patients.6

Besides shortening of SL, the observed increase in TST could be best explained by a greater improvement (increase) in the LSE compared to placebo.6

This is especially important for caregivers and families since a child who sleeps for 5 hours but wakes twice every hour is more disruptive to parents than a child who sleeps for 5 hours but wakes 10 times in the first hour. By the end of the 13-week double-blind period, the mean LSE increased on average by 77.9 minutes in the Slenyto treated group i.e., the LSE improved by over an hour.6

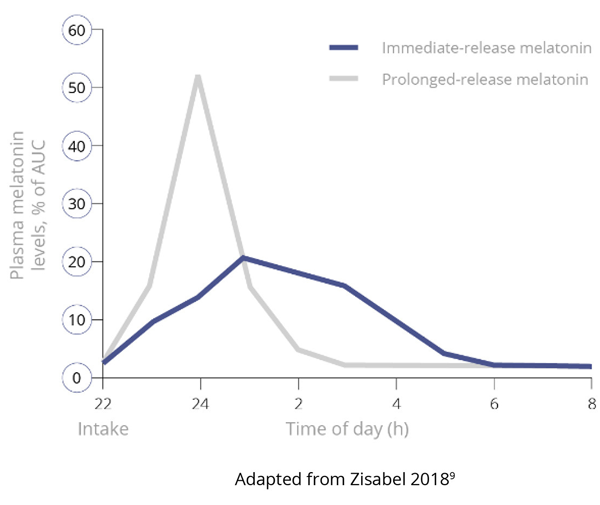

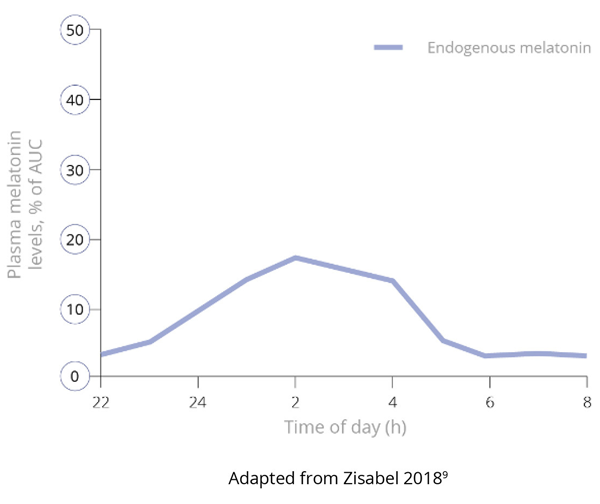

Importantly, and unlike IR melatonin, Slenyto did not result in earlier waking. In an earlier study of IR melatonin, a proportion of children fell asleep more quickly (i.e., SL was reduced) but also started to wake earlier (phase shifting).5 Slenyto improved both sleep initiation and sleep maintenance since it has been developed to mimic the endogenous profile and releases melatonin throughout the night.6 See Figure 4

Figure 4. Pharmacokinetic Profiles of Immediate, Prolonged-Release and Endogenous Melatonin*

Figure 4a. Pharmacokinetics of Immediate-Release versus Prolonged-Release Melatonin9

Figure 4b. Endogenous Production of Melatonin9

*Data derived from studies in adults

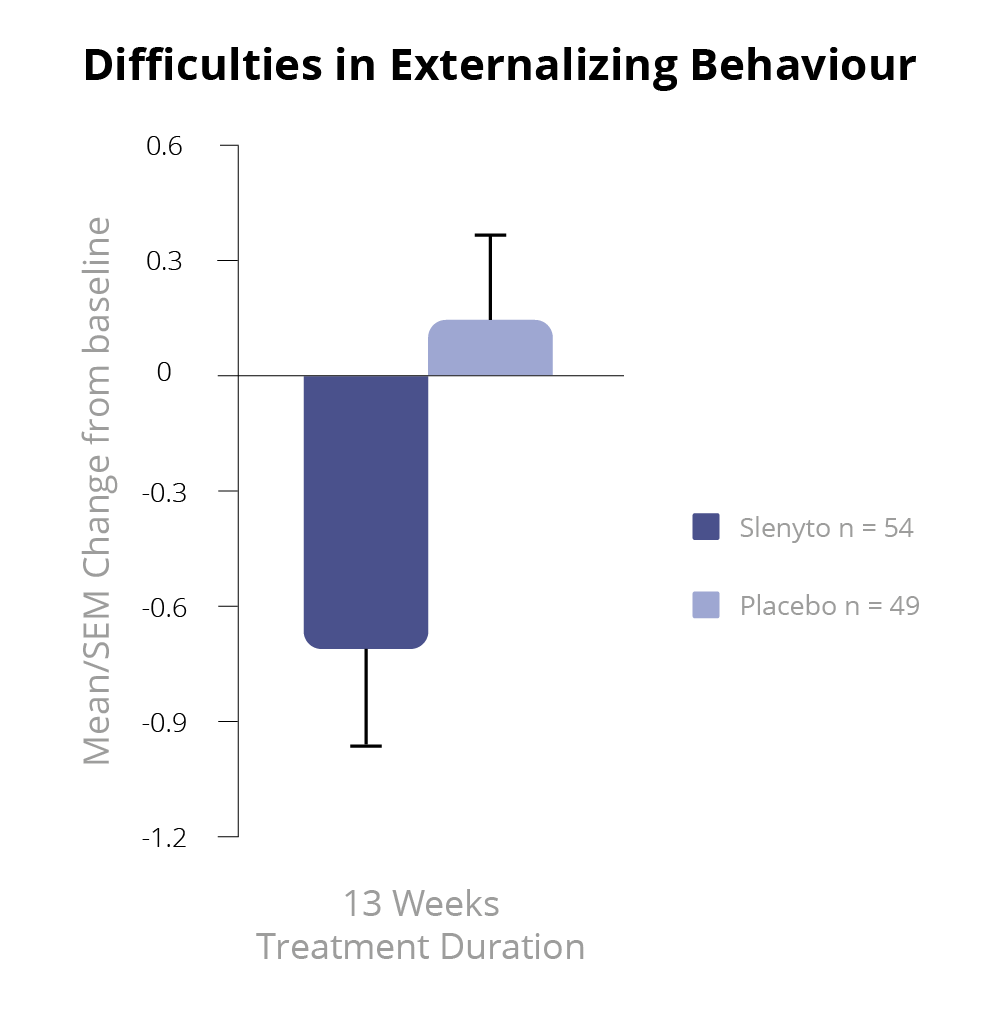

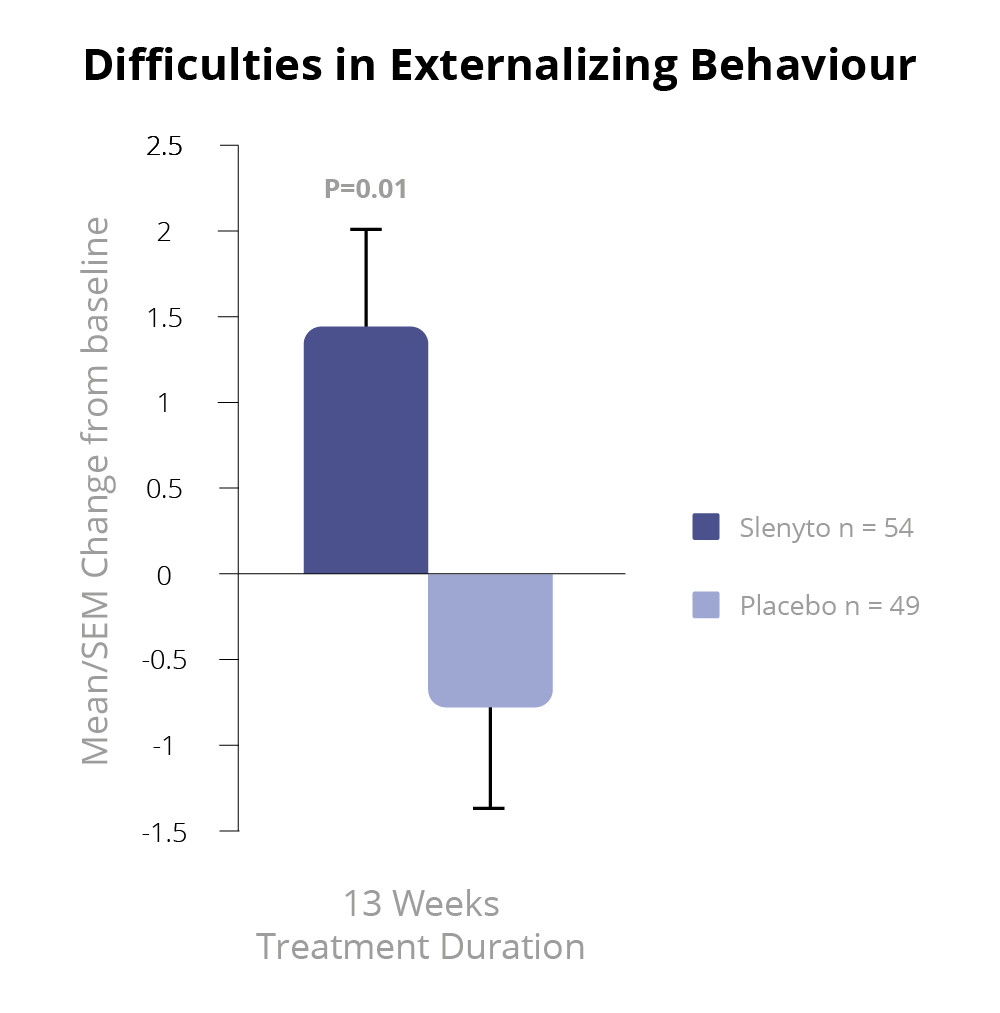

Slenyto 2 mg/5 mg treatment resulted in a significant improvement over placebo in the child’s externalising behaviours (hyperactivity/inattention and conduct scores) as assessed by the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) after 13 weeks of double-blind treatment (p=0.021)1 – See Figure 5.

Using improvement (i.e., decrease) in externalising behaviours score by 1 unit or more as a criterion of clinical response, the percentage of responders after 13 weeks of double-blind treatment in the Slenyto group was 53.7% compared to 27.7% in the placebo-treated group (Odds ratio 3.0; p = 0.008), providing evidence for the clinical meaningfulness of the treatment effect.1,7 The 26% difference in percentage between the groups corresponds to an NNT of 3.8. For the total SDQ score after 13 weeks of double-blind treatment, there was a trend to benefit in favour of Slenyto (p=0.077).

Figure 5. SDQ Externalising Behaviour During the Double-blind Period7

Schroder, C.M et al. 2019 'Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Sleep In Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Impact on Child Behaviour and Caregiver's Quality of Life', Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 49(8), 3218-30

The treatment effects on sleep variables were associated with improved parents’ well-being. There was a significant improvement with Slenyto over placebo in Composite Sleep Disturbance Index (CSDI) – assessed parent satisfaction in child sleep pattern (p=0.005) and in caregivers’ well-being as assessed by the World Health Organization scale (WHO-5) after 13 weeks of double-blind treatment (p=0.01).8

See Figure 6.

Figure 6. WHO-5 Caregiver’s Well-being and Quality of Life During the Double-blind Period8

Schroder, C.M et al. 2019 'Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Sleep In Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Impact on Child Behaviour and Caregiver's Quality of Life', Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 49(8), 3218-30

It is pertinent to ask whether the improvement in parents’ quality of life, subsequent to the improvement in a child’s sleep, might provide a "positive bias" on the parent-completed rating scales of patient behaviour or influence parenting and, therefore, behaviour of children. Yet, the change in caregivers’ quality of life seems strongly related to the improvements in daytime behaviour (total SDQ) rather than to the improvements in child’s sleep (TST, SL, or longest duration of uninterrupted sleep).

Of note, caregivers’ quality of life had already improved significantly with the Slenyto-treated compared to the placebo-treated groups after 3 weeks; by that time the hyperactivity/inattention scores also improved significantly in the Slenyto compared to the placebo-treated groups. Furthermore, caregivers’ own sleep did not improve significantly with a Slenyto-treated child compared to a placebo-treated child and improved further only months later in the open-label study.7

These findings could be interpreted as improvement of well-being of parents is mediated by improvement of daily behaviour in the child and not directly by sleep improvement in the child or parent. It is, therefore, most likely that the improvement in sleep in the subjects led to the improvement in behaviour and that this improvement is more valuable to the caregivers’ quality of life than the improvement in child sleep per se.7

The relevance of improvements in sleep to the observed improvements in behavioural attributes was demonstrated by the significant correlations between the changes in TST and duration of uninterrupted sleep with the changes in total SDQ and less so for SL.

The impact of sleep duration on behaviour can thus be explained, at least in part, by the improvement in duration of uninterrupted sleep rather than the improvement in sleep latency. This is of note because the prolonged release formulation which releases melatonin throughout the night appears to be effective in improving both sleep onset and sleep maintenance whereas immediate release melatonin formulations are reportedly as effective in sleep induction but less so with sleep maintenance.8

Of the randomised participants, 28.8% had comorbid ADHD and 12.8% had comorbid epilepsy, as determined by patient medical history. Importantly, sub-group analyses demonstrated that Slenyto was similarly effective in children with or without ADHD comorbidity.8

No unexpected safety issues were reported. Adverse effects were few and mild, with only headaches and daytime somnolence increased in the treatment group relative to placebo group. There was no increase in, or new onset of, seizures. In contrast to the usual difficulties with tablet formulations experienced by children with ASD, compliance was excellent.8

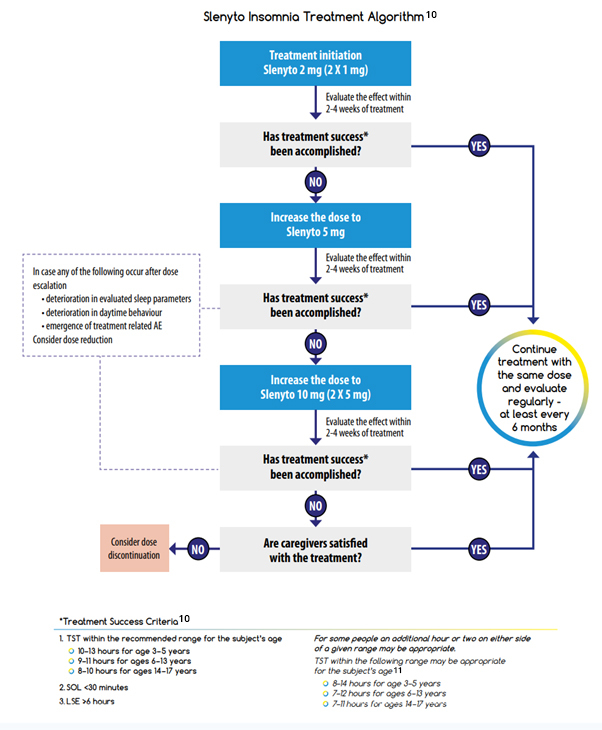

A Guide to Treatment Goals and Therapy Optimisation with Slenyto

Flynn Pharma Ltd (2022) ‘Slenyto ® Treatment Goals and Therapy Optimisation – A Guide for Healthcare Professionals’ (2022). Available at: https://flynnforum.com/education_training/slenyto-treatment-goals-and-therapy-optimisation-a-guide-for-healthcare-professionals/ (accessed: September 2024).