Prominent sleep problems include early sleep onset, repeated and prolonged awakening during the night and early sleep offset, regardless of age and sex.3

All sleep stages are present but stage 3–4 nonrapid eye movement sleep is reduced. Rapid eye movement sleep is disrupted, and arousals, with increased tonic electromyogram activity, are frequent. Awakenings (more than 15 min) occur in 75% of cases.3

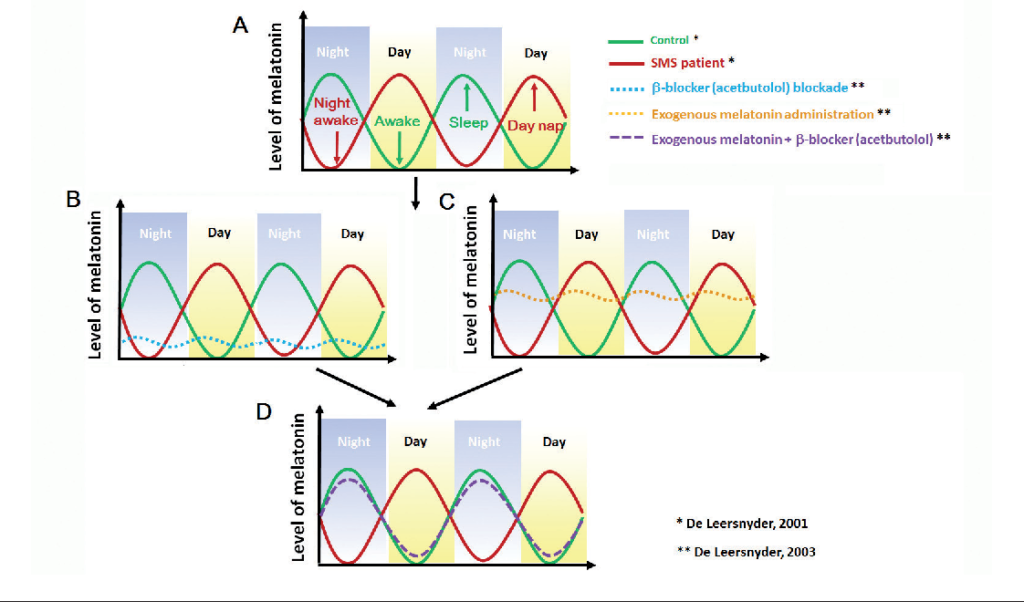

Several studies have implicated an inverted rhythm of melatonin secretion as the root cause of the sleep disturbance in SMS, providing evidence that these circadian-rhythm difficulties can complicate behaviour and learning – See Figure 2. Furthermore, individuals with RAI1 mutation also have altered melatonin secretion, implicating RAI1 directly in circadian function.2

A. The green line refers to the normal rhythm of melatonin in control individuals who have a normal sleep and awake pattern (green arrow). The red line refers to inverted rhythm of melatonin in SMS patients, who have more daytime napping and night awakening (red arrow).4

B. The blue dotted line represents the change in melatonin in SMS patients treated with β1-adrenergic antagonist acetbutolol during the day. β-blocker blockade significantly alleviates daytime melatonin peaks, but melatonin levels at night are not improved.4

C. The yellow dotted line refers to the change in melatonin in SMS patients with exogenous melatonin administration before bedtime, indicating the melatonin levels at night are elevated.4

D. The purple dotted line represents the change in melatonin in SMS patients with combined treatment with β-blocker (acetbutolol) to block endogenous melatonin production during the day plus exogenous melatonin administration in the evening, resulting in suppressed melatonin levels in the daytime and increased melatonin levels at night.4

References:

2. Williams, S.R. et. al. 2012. ‘Smith-Magenis Syndrome Results in Disruption of CLOCK Gene Transcription and Reveals an Inegral Role for RAI1 in the Maintenance of Circadian Rhythmicity’, The American Journal of Human Genetics. Volume 90, Issue 6, 941-949

3. De Leersnyder, H. 2006. ‘Inverted rhythm of melatonin secretion in Smith-Magenis syndrome: from symptoms to treatment’, TRENDS in Endocrinology and Metabolism. Volume 17, Issue 7, 291-298

4. Chen, Li. et. al. 2015. ‘Smith-Magenis syndrome and its circadian influence on development, behaviour, and obesity – own experience’, Developmental Period Medicine. Volume 19, Issue 2, 149-56